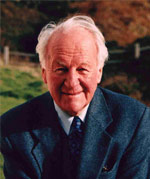

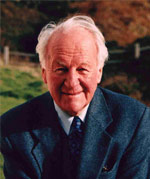

Wednesday this past week (27th July) saw the death of the Rev John Stott at the age of 90. In 2005, Time magazine named Stott as one of the 100 most influential people in the world then living. This may seem far-fetched, since, although John Stott is a prominent figure in certain Christian circles, he is not a household name to the world at large. However, if we are thinking in terms of influence rather than fame it does seem plausible to me, since his writing, preaching and personal encouragement have been formative in the lives of thousands of Christian leaders around the world, whose own ministries have thus borne the marks of Stott’s influence and in their turn have shaped the lives of millions of Christians, at least some of whom have made substantial positive contributions to wider society.

Wednesday this past week (27th July) saw the death of the Rev John Stott at the age of 90. In 2005, Time magazine named Stott as one of the 100 most influential people in the world then living. This may seem far-fetched, since, although John Stott is a prominent figure in certain Christian circles, he is not a household name to the world at large. However, if we are thinking in terms of influence rather than fame it does seem plausible to me, since his writing, preaching and personal encouragement have been formative in the lives of thousands of Christian leaders around the world, whose own ministries have thus borne the marks of Stott’s influence and in their turn have shaped the lives of millions of Christians, at least some of whom have made substantial positive contributions to wider society.

John Stott will be remembered for many things, variously emphasised in the numerous obituaries and tributes he has received. These include his over fifty books, his ministry to the same London parish (in various capacities) from his ordination in 1945 until his death, his conviction that Christians should be involved with issues of justice and social concern, and his worldwide travels encouraging and training Christian leaders particularly in the majority (non-Western) world. Taken together, the obituaries in the Daily Telegraph and Christianity Today give fairly good overviews of his life.

I thought I’d talk a little about one of the aspects of John Stott’s thought that has become increasingly important to me over the past year. This is his concept of “double listening”:

I believe we are called to the difficult and even painful task of ‘double listening’. That is, we are to listen carefully (although of course with differing degrees of respect) both to the ancient Word and to the modern world, in order to relate the one to the other with a combination of fidelity and sensitivity.

(John Stott, The Contemporary Christian: An urgent plea for double listening (IVP, 1992), p. 13)

Stott had a firm conviction that God has made himself known in the person of Jesus Christ, and that this divine revelation can be accessed particularly through the words of the Bible as unfolded to readers by the Holy Spirit. Christians thus need to pay careful attention to this divine revelation, which should shape how they perceive all of life. However, Stott believed that having lots of Bible studies was not sufficient to enable Christians to engage constructively with the people around them or with wider society. For this, Christians need truly to listen to the people we meet, and to the experiences, ideas, aspirations and fears of our time expressed in books, journalism and entertainment media. Stott also insisted that that although Christians should be firm in their convictions, we need to empathise with the way the world is experienced by our fellow human beings, even if we have points of disagreement with them, rather than taking the first opportunity to jump on them with pre-packaged answers:

It is a truism to say that we have to listen to the Word of God, except perhaps that we need to listen to him more expectantly and humbly, ready for him to confront us with a disturbing, uninvited word. It is less welcome to be told that we must also listen to the world. For the voices of our contemporaries may take the form of shrill and strident protest. They are now querulous, now appealing, now aggressive in tone. There are also the anguished cries of those who are suffering, and the pain, doubt, anger, alienation and even despair of those who are estranged from God. I am not suggesting that we should listen to God and to our fellow human beings in the same way or with the same degree of deference. We listen to the Word with humble reverence, anxious to understand it, and resolved to believe and obey what we come to understand. We listen to the world with critical alertness, anxious to understand it too, and resolved not necessarily to believe and obey it, but to sympathise with it and to seek grace to discover how the gospel relates to it.

(The Contemporary Christian, pp. 27-28)

In connection with this, Stott quotes Archbishop Michael Ramsey:

We state and commend the faith only in so far as we go out and put ourselves inside the doubts of the doubters, the questions of the questioners and the loneliness of those who have lost their way.

(Michael Ramsey, Image Old and New (SPCK, 1963), p. 14)

This model has acquired a greater resonance for me living in North America for the past year, where in certain social settings, particularly in academia, hostility towards Christianity is aroused partly by Christians being associated with the strident voices of one pole of the “culture wars”. (Several friends have heard me ramble repeatedly about my dislike of the whole culture wars paradigm, so I won’t inflict that on you here.) In this context, it is perhaps especially important that Christians should learn to listen and to engage in genuine conversation rather than simply shouting across the barricades.

On the other hand, however, my impression is that many Canadian Christians, perhaps especially in Toronto, are so concerned not to conform to this negative stereotype of Christians as preachy right-wing crazies that they are often afraid to voice their convictions at all or even to own up to being a Christian. I feel that I have succumbed to this fear myself on occasion in the past year (more so than when studying in the UK, which is a fairly secular country) and ducked away from expressing my true self even when these matters have naturally arisen in conversation. It’s a difficult balance, as I think that there is a legitimate prudence in not always putting all our cards on the table straight away where this does not seem helpful, but I fear that to conceal one’s core convictions indefinitely is damaging to a sense of personal integrity.

Thinking about Stott’s model of double listening started me thinking more widely about the nature of conversation and how the interplay between listening and speaking says something important about the ethics of communication. This is not exactly the same topic which Stott was addressing, though it is related, and these broader thoughts might perhaps be more readily accessible to those reading this who may not share the Christian convictions presupposed by Stott’s model.

Conversation involves interacting with another person, and so necessarily entails acknowledging that other person, at least to a minimal degree. The rhythm of conversation, its ebb and flow, embodies a principle of giving space to another person, letting them be who they are and express how things look from the place where they are standing, before responding with something of who we are and how we see things. Though the content of our conversation might legitimately affirm, challenge, or gently nuance what we hear from the other person, the prior condition of true conversational engagement is an acknowledgement of the other person as a person. Communion is the prior condition for communication.

Those who are truly gifted in the art of conversation seem to have a way of drawing out the other person, engaging in a dance whose moves aim to allow the other person to reveal something of themselves. Those with this gift seem to want not so much to unload onto the other person what they find interesting as to find those keys which will unlock the other person and so allow the other person to unfold to reveal themselves to be the profoundly fascinating person that they are (as pretty much everyone seems to be if you can ask the right questions). It seems that the best conversationalists combine a skill (partly a natural endowment and partly a skill which can be learned and improved) with a true interest in and care for the other person which has an ethical dimension.

This is an area where I feel that I often fail. As a child and a teenager, I didn’t see the point of small talk. I mean, why bother talking about the weather or what the other person did at the weekend (which never seemed all that earth-shattering) when there were far more significant things to discuss, like Shakespeare, or electoral reform, or predestination? As part of my belated learning of social skills at university, I came to realise that the point of small talk is not usually the actual topic of conversation, but rather, it’s a way of acknowledging the presence of the other person and forging a connection based on our shared humanity.

However, I think I still have a way to go in learning to be a good conversationalist who is able to affirm and draw out the other person in the way I engage with them. I think where I derail as a conversationalist now is particularly once we’ve moved past the small talk onto those topics that interest me, onto books, ideas, theology, politics and the like. The trouble is that if my mind gets onto a topic I am interested in, about ten different thoughts come to mind, and I feel a compulsion to share all of them, which makes my contribution to conversation resemble a lecture to which the other person doesn’t have space to respond (or a sermon, depending on the topic of conversation). Alternatively, I share one or two of my thoughts but then get frustrated that the topic of conversation moves on and I didn’t get to say what I really wanted to say, and so am inclined to want to parachute it in somewhere later, whether or not it’s really of interest to the other person.

Occasionally this is because my conversation partner says something I disagree with and I feel the need to correct them prematurely rather than having the grace to give them space to reveal themselves before discerning whether or not it would be helpful to that person at that moment to prompt their thinking in a different direction. (This is more directly related to Stott’s idea of double listening.)

More often, though, I don’t want to shut the other person down. I just get so carried away with my excitement with the subject of conversation that I don’t give space to truly hear the other person’s contribution. Sometimes I go away from a conversation or replay it later lying in bed and am frustrated that I didn’t get to hear as much from the other person as I would have liked. If you are someone I have done this to, I am sorry. I am still learning the art of conversation and appreciate that you have the grace to give me space to learn, despite my mistakes.

I would like to conclude by returning to John Stott, but to his thoughts on a different topic. In my quest for his thoughts on “double listening”, I borrowed a number of his books from one of the college libraries here in Toronto, including his final book, The Radical Disciple: Some Neglected Aspects of Our Calling (IVP, 2010). This book was intentionally written as a farewell – it has a postscript which begins “As I lay down my pen for the last time (literally, since I confess I am not computerised)” (p. 137). The book is pretty readable and most of the chapters are only 10 to 20 pages long, with the small format of the book meaning that there are not that many words to a page. The chapter titles indicate areas which Stott feels are important to following the way of Christ but to which Christians today may not give as much attention as they should: Nonconformity, Christlikeness, Maturity, Creation Care, Simplicity, Balance, Dependence, Death.

There is an obvious and presumably deliberate poignancy to ending with a chapter on death. However, perhaps the most moving chapter is the penultimate one on dependence, in which Stott begins by recounting the experience of a fall which put him in hospital on a day he was due to preach. The chapter ends with this reflection:

We come into this world totally dependent on the love, care and protection of others. We go through a phase of life when other people depend on us. And most of us will go out of this world totally dependent on the love and care of others. And this is not an evil, destructive reality. It is part of the design, part of the physical nature that God has given us.

I sometimes hear old people, including Christian people who should know better, say, “I don’t want to be a burden to anyone else. I’m happy to carry on living so long as I can look after myself, but as soon as I become a burden I would rather die.” But this is wrong. We are all designed to be a burden to others. You are designed to be a burden to me and I am designed to be a burden to you. And the life of the family, including the life of the local church family, should be one of “mutual burdensomeness”. “Carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfil the law of Christ” (Galatians 6:2).

Christ himself takes on the dignity of dependence. He is born a baby, totally dependent on the care of his mother. He needs to be fed, he needs his bottom to be wiped, he needs to be propped up when he rolls over. And at the end, on the cross, he again becomes totally dependent, limbs pierced and stretched, unable to move. So in the person of Christ we learn that dependence does not, cannot, deprive a person of their dignity, of their supreme worth. And if dependence was appropriate for the God of the universe, it is certainly appropriate for us.

(The Radical Disciple, pp. 110-11)